There is a peculiar tension at the heart of contemporary Western culture. We have inherited a set of moral Christian foundations. Foundation that says that every human being possesses inherent dignity, that the suffering of strangers should concern us, and that power ought to serve the vulnerable rather than exploit them (which most of us take to be self-evident).

Yet the philosophical and theological framework that generated these moral intuitions has, for many, become hard to follow due to its reliance on the belief in God. In our modern world, we now have an important question about whether the fruit (the moral and ethical values) can survive once we have pulled up the root.

Christian atheism represents one answer to this dilemma. It is the claim that the ethical core of Christianity can be preserved, and indeed must be preserved, even after we have abandoned belief in a supernatural God. This position strikes many as an incoherent contradiction in terms. But I want to suggest that it deserves some consideration, both as a philosophical stance and as a practical orientation toward life.

The Death of God and What Remains

The phrase “death of God” entered philosophical conversation through Nietzsche. Sadly, he is often misunderstood on what he meant at the time. For Nietzsche, God’s death was a cultural event: the collapse of the moral and ethical foundations that had supported Western morality for two millennia. He saw this clearly and predicted, correctly, that most people would not grasp the inherent risk in this for many generations.

The “Death of God” theologians of the 1960s, Thomas Altizer, William Hamilton, and Paul van Buren, took this diagnosis as their starting point but reached different conclusions. Altizer, the most radical among them, argued that God had literally died in the crucifixion of Christ. The God of classical theism had emptied himself completely into the world, leaving behind a transformed world as a result. This meant that there is no longer any God to worship but a pattern of existence to embody: self-giving, solidarity with the suffering, and love without conditions.

This is a fundamental reorientation with Christianity. Traditionally, theism suggests a God who exists independently of the world, who created it and sustains it, and who will ultimately judge it. Christian atheism dispenses with all of this. There is no cosmic overseer, no divine plan, and no afterlife in which accounts will be settled. There is only this world, these lives, this moment, and the question of how we ought to live within them.

What Remains When Belief Departs

If we strip away the supernatural elements of Christianity, things like the virgin birth, the miracles, the resurrection, and the promise of eternal life, what remains? A great deal, as it turns out.

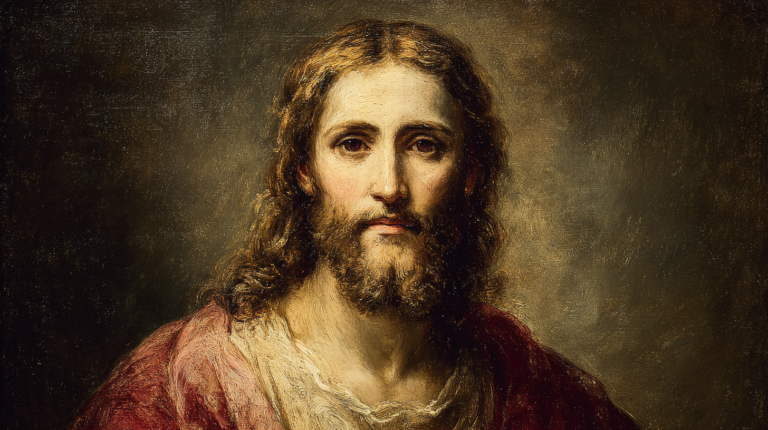

First, there is an ethical vision of remarkable power. The teachings attributed to Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels constitute one of the most demanding moral programs ever articulated. Love your enemies. Do good to those who hate you. Turn the other cheek. Give to everyone who asks. Judge not. Forgive without limit. These are not just difficult; they cut against the grain of human nature in ways that remain genuinely radical after two thousand years.

Second, there is a particular stance toward power, wealth, and status. Jesus consistently sided with the marginalized against the respectable, with the poor against the rich, and with sinners against the righteous. He reserved his harshest criticism not for the obvious wrongdoers but for the religious authorities who used piety as a means of social control. This critique of institutional religion—delivered from within a religious tradition—retains its force regardless of one’s metaphysical commitments.

Third, there is what we might call an existential orientation: a way of confronting suffering, mortality, and the apparent meaninglessness of existence. The crucifixion stands at the center of Christian symbolism, not despite its horror but because of it. Here is a vision that does not flinch from the worst that life can offer, that finds meaning not in escaping suffering but in how one bears it.

None of this requires belief in God. One can recognize the ethical value of the Sermon on the Mount without believing that its author was divine. One can find the crucifixion narrative deeply meaningful without believing in the resurrection. One can participate in Christian community and ritual while remaining agnostic or atheist about the metaphysical claims that traditionally accompanied them.

The Philosophical Case

The objection will immediately arise: without God, what grounds these ethical commitments? Why should we love our enemies? Why should we care for the poor? If there is no divine lawgiver, no cosmic justice, and no ultimate accountability, then on what basis can we claim that these teachings are binding?

This objection, though common, rests on a confusion. The question of whether God exists is logically independent of the question of whether Christian ethics are valid. Even if God exists, we would still need to determine whether his commands are good, unless we are prepared to say that whatever God commands is good by definition, a position that generates well-known difficulties. And if we can recognize goodness independently of God’s commands, then we do not need God to ground our ethics.

The Stoics, whom I have spent much of my career studying, developed a sophisticated ethical system without reference to a personal God. They grounded ethics in human nature and reason, arguing that virtue is its own reward and that we have duties to one another as fellow rational beings. Something similar is available to the Christian atheist. We can ground the ethics of Jesus in considerations of human flourishing, in the recognition of our shared vulnerability, and in the simple fact that suffering is bad and its alleviation is good.

Moreover, there is something to be said for an ethic that does not depend on supernatural reward and punishment. If I refrain from cruelty because I fear hell or practice generosity because I hope for heaven, there is something deficient in my moral motivation. The Christian atheist loves her neighbor not because God commands it, not because she will be rewarded for it, but because she has come to see that this is what human beings owe to one another. This is, arguably, a purer form of moral commitment than one contingent on divine surveillance.

The Practical Question

Philosophy, to me, is not limited to an intellectual exercise. As the ancients understood, it is a way of life, a set of practices and disciplines aimed at human flourishing. The relevant question is not only whether Christian atheism is logically coherent but also whether it is liveable.

Here we must be honest about the difficulties. Christianity has always been more than a set of teachings; it is a community, a tradition, and a form of life sustained by shared beliefs and practices. Can one participate authentically in this tradition while rejecting its central religious claims? Will the practices retain their meaning and power once divorced from the beliefs that originally created them?

These are genuine concerns. There is something parasitic about enjoying the fruits of a tradition while refusing to accept its foundations. And there is a real question about whether Christian ethics can survive indefinitely without Christian theology, whether the moral intuitions that Christianity has given to us will slowly erode once their original justification has been abandoned.

Yet traditions are not static. Christianity itself has always been a site of development, absorbing influences from Greek philosophy, Roman law, Germanic culture, and countless other sources. The Christianity of Thomas Aquinas is not the Christianity of Paul; the Christianity of contemporary Quakers is not the Christianity of medieval Catholicism. Traditions survive by adapting, and Christian atheism might be understood as one such adaptation, an attempt to preserve what is valuable in the tradition while acknowledging what can no longer be believed.

Conclusion

I am not arguing that everyone should become a Christian atheist. For those who genuinely believe in God, who find in traditional Christianity a coherent and compelling worldview, there is no reason to abandon that belief just because others cannot share it.

But for those of us who cannot believe, who have looked honestly at the evidence and found the case for theism unconvincing, the question remains: what do we do with the tradition that has shaped us? One option is simple rejection, a clean break with the religious past. Another is the kind of vague spirituality that affirms nothing in particular. Christian atheism offers a third path: serious engagement with the Christian tradition on terms that do not require the belief in something that we can’t bring ourselves to believe in.

This is not a comfortable position. It satisfies neither the orthodox believer nor the militant atheist. It requires living with some level of tension and ambiguity. But perhaps this is simply the human condition. We did not choose to be born into a world without clear answers to the most important questions. We can only decide how to live within it.

The teachings of Jesus offer one answer, not the only answer, but an interesting one. That we can no longer believe the author was God does not mean we cannot still learn from them.